In the ’80s, Peruvians in rural areas largely used to exchange goods to meet their food requirements. The main crops were corn, yuca and bananas.

Yet, the introduction of coca cultivation changed this mentality by bringing money into the community. With coca production, businesses emerged and the development of the village associated with this new crop. However, the introduction of coca also had a negative impact on the environment as deforestation made way for new coca plantations. It also encouraged the emergence of terrorism and drug trafficking, creating an atmosphere of insecurity in the Juanjui region.

In 1995, in order to restore peace in the province, an anti-drug program was launched in collaboration with the United States‘s international cooperation. One of the measures taken was to drop, using helicopters, capsules of noxious mushroom fungi. However, this method also destroyed the flora and fauna of the area, leading to an environmental disaster. The local people faced famine as there were no alternative crops to fall back on. For three years, the region’s economy was one of subsistence, with producers struggling for survival.

In 1997, the government set up an alternative development program to help the Juanjui district. This program supported farmers in the creation of coffee plantations in the mountains and cacao production in the valley. During this period, there was massive support in the fields, creating a positive economic dynamic. Namely, families were able to send their children to school and enjoyed a more stable standard of living thanks to their integration into a fairer market. Today, new generations, with their university education, are helping to improve crop yields and meet today’s environmental challenges.

Moreover, one of the organizations of farmers that arose in 2017 was the Cuencas del Huallaga cooperative. This cooperative, founded on the values of transparency and integrity, helps cacao producers in their development. In the beginning it was Melvi Tocto, the founder of the cooperative, who took the initiative to help coffee growers. At the beginning, there were only 15 members in the cooperative. Today, it includes eleven zones in the province of San Martin, it owns two storage warehouses for dry cacao and has over 520 members spread over over 2,000 hectares.

The Fairtrade premium is distributed as follows:

| Price for a tonne of Organic and Fairtrade cacao: Price per tonne (05/05/2023): $3060 Fixed premium Fairtrade: $240 per tonne Fixed premium Organic: $300 per tonne Total: $3600 per tonne |

30% of the premium is allocated to the producers, this amount being included in the purchase price paid to the farmers. Producers are free to invest this share as they see fit, but the cooperative makes them aware of the importance of investing in the agricultural circular economy.

40% of the premium is invested in crop productivity (in accordance with standards, an investment of at least 25% in this sector is legally required). This enables the agronomic technicians who support the producers in the field.

20% of the premium is invested in the association’s infrastructure.

The remaining 10% is allocated to representation initiatives, at fairs and assemblies.

Initiatives implemented thanks to Fairtrade premium:

In the region of San Martin, around 40% of the crops is cacao, 30% is rice, 10% is coffee and another 10% is maize. Cacao production in the area has a yield of 1120 kilograms per hectare.

In recent years, cacao growers have witnessed an increase in diseases affecting cacao trees. The changing climate has blurred the once-distinct seasons, leading to favourable conditions for diseases such as Monilia and Phytophthora to thrive. It has also led to a proliferation of pests and fungi, all resulting in a substantial decline in agricultural yields. Additionally, inadequate knowledge in machinery operation has detrimental effects on plantations. Some growers unintentionally damage cacao tree trunks, making them more susceptible to fungal infections and other parasites.

Moreover, problems with contamination of pesticides, herbicides and insecticides mainly stem from neighboring maize and rice farming. Sometimes, cacao growers whose fields are heavily contaminated can no longer obtain Organic certification and are forced to abandon their farms. A concrete case occurred in Sisa de Huallaga, where the cooperative was forced to close this area to Organic trade.

To control potential contamination by non-organic crops, with the help of agricultural engineers, the cooperative carries out daily checks on the farms. They have already implemented various measures, such as:

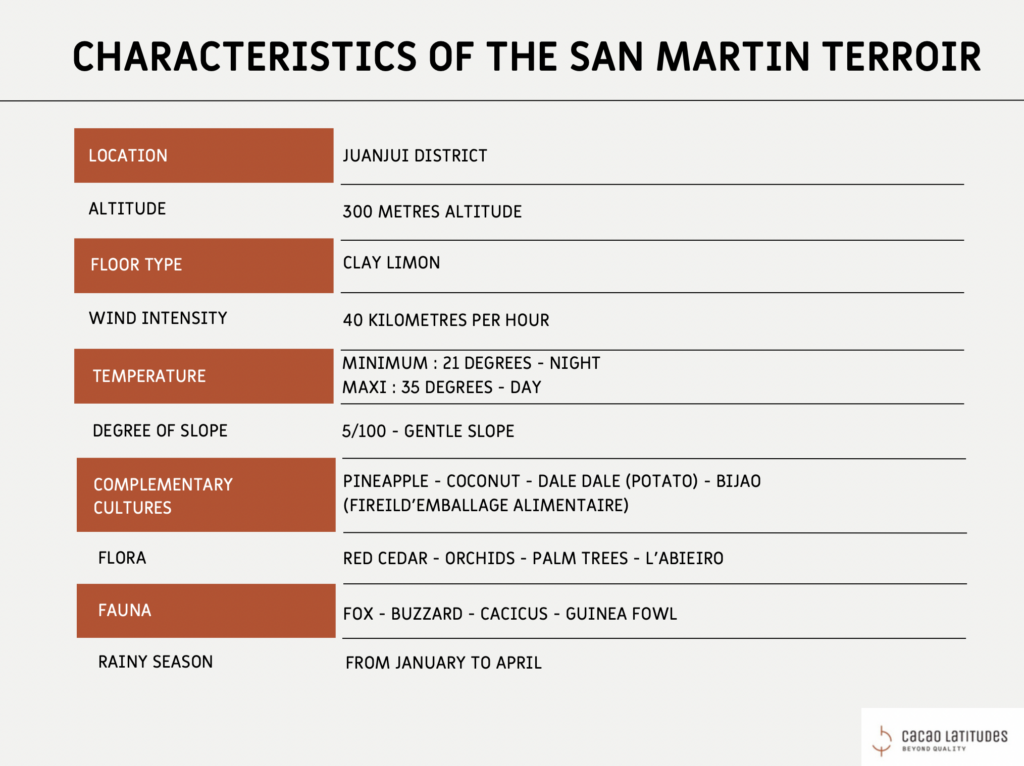

The term “terroir,” derived from the word “earth,” first appeared in the 12th century. It refers to a natural region where agricultural products are cultivated. A combination of factors contributes to creating unique organoleptic characteristics in the final product.

In the year 2023, the cooperative started to focus on the study of organic insecticides to combat pests that damage the plants. Two agronomic engineers will conduct tests on three different plants using various methods. These methods include decoctions, fermentation and extraction.

The three plants under study are Neem, Castor Bean, and Dieffenbachia, which possess insecticidal properties for creating an entirely natural product. Starting from the month of August, once the liquids are obtained, tests will first be conducted on leaves harvested from the fields to observe the plants’ reactions. Subsequently, tests will be carried out in a dedicated study area, which has been cleared of all other insecticides to avoid biasing the results.

If any of the natural insecticides prove effective, the engineers will then need to determine the optimal dosage of the pure liquid with water to maximize the project’s profitability by producing larger quantities of the liquid.

The ultimate goal is to conduct a comprehensive study to establish a solid foundation for using these insecticides independently across the 2000 hectares of land. By producing its own insecticide, the cooperative will be able to break free from the expensive system of purchasing pesticides from the market, while maintaining complete control over its composition to ensure greater transparency.

Furthermore, this approach will enable the cooperative to achieve significant cost savings. Purchasing an organic product from the market is an investment for producers, as it costs twice as much as a chemical insecticide. These savings can be reinvested in other projects beneficial to the cooperative.

To explain more about the historical context of the region of San Martin, Justine Chesnoy, Cacao Latitudes’ founder, wants to share the story of Martiza Truijillo. Justine worked closely with her for 4 years in Peru when she was ECOM Peru manager at that time.

Martiza, ECOM Director of Sustainable Development and Certification of cacao and Coffee in Peru, was born in the Huánuco region. Like many other remote areas of Peru, Huánuco experienced a wave of drug-related military violence and terrorism in the 1980s.

“Where there’s drugs, there’s terrorism.”

Maritza’s parents were farmers. Even though they did not grow coca, almost all the surrounding fields did. At that time, explains Maritza, there were small villages in the middle of nowhere where the American dollar ruled. The majority of this money was spent on alcohol and prostitution; food had to be imported.

Drug-related terrorism led to thousands of deaths, both at the hands of drug traffickers and the army. “One day, soldiers came to my village and killed all the adults,” says Maritza. “The army believed they were helping the narcos. My parents were out running errands, but they killed my uncle. I was ten years old.”

In the early 2000s, Peru’s government established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The UN and USAID granted funding to eradicate the country’s coca fields and convince farmers to switch to alternative crops, namely coffee and cacao.

After completing her studies in agronomy, Maritza joined the alternative development to coca project, where she worked with nearly 120 producers. While these farmers were keen to finally have peace of

mind, getting them to accept the change was no easy feat. Coca can be harvested within six to eight months, whereas cacao needs two to four years depending on the variety. In the end, 75% of the producers chose to plant a cacao hybrid known as CCN-51 because it grows quickly, adapts well to weather conditions, produces high yields, and resists disease.

Another challenge was convincing the farmers to stop cutting down trees. The majority were also cultivating corn, which requires deforestation. Cacao trees, on the other hand, grow into perennial forests.

“It was a whole awareness-building process.”

Today, the social and environmental impacts are tangible. Not only have forests returned to the ecosystem, but the local communities’ lives have also completely changed. “Today, the producers aren’t necessarily making more money, but they have a better quality of life,” says Maritza. “Income distribution has changed. For instance, parents send their children to school. Women, who were once confined to their homes on the pretext of safety, now participate in decision-making. Their role is valued.” In the end, replacing coca with cacao transformed the entire local economic and social system.

Copyright © 2024 Cacao Latitudes | Conditions of Use | Cookie Policy